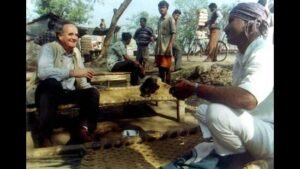

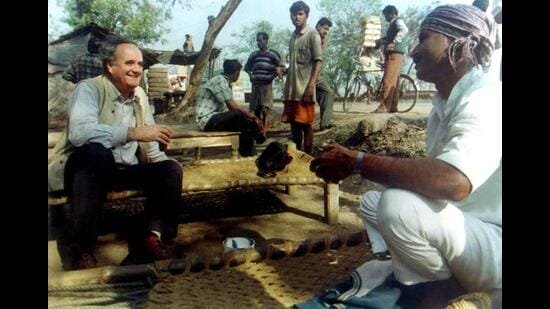

It was often said that once upon a time, people across vast swathes of rural India did not believe the news of election results until they heard it from Mark Tully on BBC Radio. The legendary broadcaster and journalist died in New Delhi a day before India’s 77th Republic Day at the age of 90, having covered most of the country’s seminal events in the decades before. Generations of Indians held him in great respect, even reverence, for his authentic journalism, the reports delivered on BBC radio in his calm, reassuring voice and his unwavering commitment to deliver the news as it was. No screaming and screeching, hyperbole or showmanship, his was journalism as it should be, direct, in-depth and grounded in facts. During his storied career, Sir William Mark Tully, often called Tulli saab by villagers, covered a considerable part of modern India’s history.

His top-drawer coverage of the Bhopal gas tragedy, Operation Blue Star, the shameful destruction of the Babri Masjid, the horrific riots that followed and before that the Emergency and its excesses, showed him for the extraordinary journalist that he was. For his Emergency coverage, he was expelled from India for a while.

Tully was born in Calcutta in 1935 during the Raj, and it was his interest in local languages that led to his fluency in Hindi, the envy of other foreign correspondents in Delhi. Tully studied history and theology at Cambridge and was on his way to join the clergy. His change of heart was to be journalism’s great gain. In 1965, he came to India as an administrative assistant at the BBC, and there was no looking back for him.

Having spent the greater part of his life in India, after he retired from active reporting, he was nowhere more happy than being in the India International Center or the Delhi Gymkhana discussing the evils of caste and communalism, on which he had very strong views that he was only too willing to express. These views came from his travels across India to remote villages and hamlets by local transport, a true newsman of the masses.

For 20 years, Tully headed the Delhi bureau of the BBC in the golden era of that institution, from where he covered not just developments in India but in the neighborhood — the creation of Bangladesh, the occupation of Afghanistan, the upheavals in Pakistan, the civil war in Sri Lanka and many more. He had a deep understanding of the Indian ethos and was empathetic to the people he spoke to. His journalism was informed by the vast array of people he interacted with on the ground. He wrote several books on India, the most famous perhaps being No Full Stops in India (1988). Other works include The Heart of India (1995), India in Slow Motion (2002, co-authored with Gillian Wright) and India: The Road Ahead (2011). Sharp and succinct, his literary output made him a favorite at seminars and discussions in the Capital and outside and at the many literary festivals which have now sprung up.

Though sought after by the powerful in the Capital’s elite circles, he remained untouched by the adulation that was often heaped upon him. He neither sought nor accepted any favors from the powers that be, despite living in the courtier-like culture of Delhi for so many years.

Much as he was respected in India, his relationship with the BBC began to wear thin, and he eventually left the organization in the early nineties. He was unhappy with what he regarded as too many compromises made by the BBC, and the BBC found his candour and criticism uncomfortable.

However, he did not leave India and stayed fully engaged in Indian politics, culture, literature and art, among other things, along with his partner Gillian Wright, herself a formidable scholar and fluent Urdu speaker. There was no dearth of awards for Tully, among them a knighthood from Britain, the Padma Bhushan and the Padma Shri from India, his adopted homeland. He was a valued columnist for this newspaper, his lucid raconteur-style prose winning him a vast following. He enriched our pages on Sunday with his easy, fireside chat way of writing, and we had all hoped that he would recover from his bout of ill-health and restart his remarkable contributions to our pages again. That was not to be.

He wore his immense achievements lightly, was respectful but never subservient to authority, was generous with his time and knowledge to younger journalists and students and was famous for his sparkling wit and humor. A voracious and eclectic reader, Tully once spoke to me about his admiration for the works of Thomas Merton, the theologian-monk-author. It was Merton who said, “We must make the choices that enable us to fulfill the deepest capacities of our real selves.” Tully made those choices, and we are all the richer for it.

The views expressed are personal