Accepting women’s equal right to space (Indore Molestation case: Accepting women’s equal right to space)

When two Australian cricket players stepped out of their hotel in Indore to stroll down to a nearby café, they ended up inadvertently experiencing what Indian women do every day: Street sexual assault.

Some still call it eve-teasing as if it’s some cute misdemeanor. This is not a new story but an old one. Back in the day, when I took the university special bus to college, some students carried safety pins in their bags to discourage men from getting too close. I’m told women still carry them.

Kalpana Vishwanath, the co-founder of an NGO for safer cities called — no surprise — Safetipin says things are changing with women more likely to speak up and police more willing to see this as the crime it is. But “outraging the modesty of women”, the category under which the National Crime Records Bureau records street sexual assault remains the second most reported crime, after domestic violence, with 83,891 cases reported in 2023.

Because he targeted international players at an international event — country’s prestige etc. — Aqeel Khan, the accused has been arrested with great alacrity and will undoubtedly face the full extent of the law. But, India’s abysmal ranking on women’s safety in various surveys is hardly a secret: Ninth most dangerous by World Population Review’s 2024 Women Danger Indexfour out of 10 women feel unsafe in the 2025 National Annual Report and Index (NARI) on women’s safety.

It’s only when a foreign national gets molested and posts about it, the South Korean vlogger, for instance, who was harassed by two men in Mumbai while she was live-streaming in December 2022, that media and the administration wakes up and swings into action with arrests and denunciations about behavior that goes against the grain of. guest devo bhava,

Meanwhile, Madhya Pradesh cabinet minister Kailash Vijayvargiya wants to know why the Australians hadn’t informed security and protocol before stepping out of their hotel. Seriously? For a stroll that would anywhere in the civilized world be regarded as routine? And what about the rest of us who live here and encounter this daily? Who do we inform? Sadly, this deflecting of blame is pretty predictable. Just weeks ago West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee asked why a woman medical student who had been raped had stepped out of her hostel “late at night” for dinner at 8 pm.

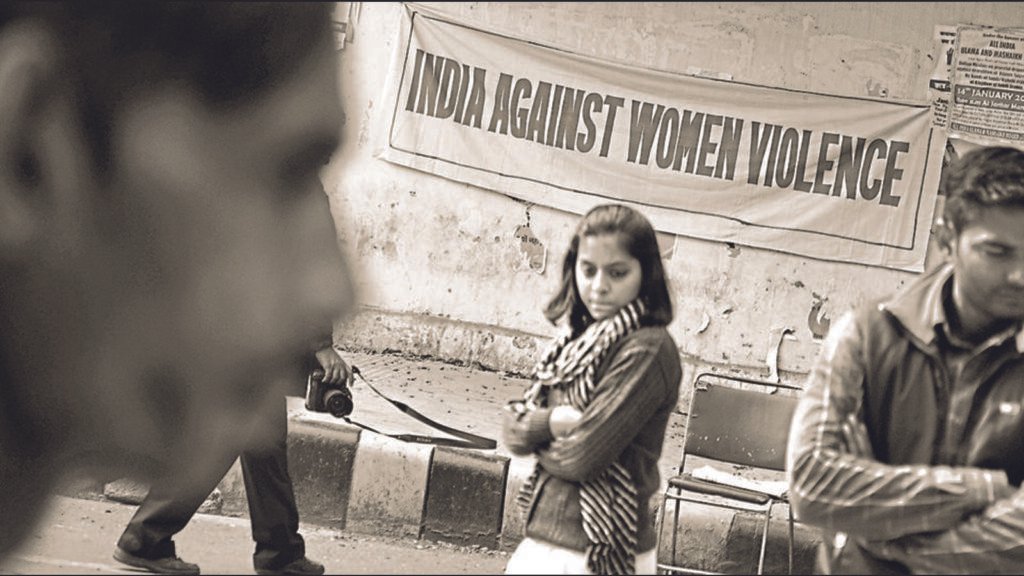

Part of the problem is a piecemeal response to high-profile incidents, the 2012 gang-rape, Kathua, Hathras, rather than a push for mindset change. We have tough laws, but poor implementation. We have fast-track courts but cases and appeals drag on for years. We have Nirbhaya funds that go unutilised. We have helplines and one-stop centres, many of which don’t function. We teach kids about “bad touch” but not about consent and autonomy of women. Boys are brought up with a sense of entitlement to believe that public spaces are off limits for women and girls.

When a patriarchal society sees a woman step beyond the Lakshman Rekha of her home and hearth it assumes she is “asking for it”. And, so the questions, why was she out so late, why didn’t she inform security? These questions are out of step with a generation of aspirational women fighting for opportunity in education, in the workplace and even for leisure. In policy and our politics we talk about women power (women power) and how female workforce participation can boost the country’s GDP. But first we must ask a simpler question: Are we prepared to see women as equal citizens with an equal right to space?

Namita Bhandare writes on gender. The views expressed are personal