Marriage is having a bit of a moment in the news cycle. If Jaya Bachchan, married for 52 years, told journalist Barkha Dutt that marriage is an outdated institution, then her colleague, Kajol suggested it should come with an expiry date with an option of renewal.

Just days earlier, Upasana Kameini Konidela was interacting with students at IIT, Hyderabad when she asked a question: How many wanted to get married? More men than women raised their hands. “The women seemed far more career-focused,” she remarked on X.

Clickbait? Hardly. These stray remarks are backed by global trends where marriage rates are plunging, with the decline being led by women who are clocking out, leading to what Financial Times called a “relationship recession” in January this year.

In China, where an authoritarian government junked its one-child policy adopted in 1979 and junked in 2015 to boost declining fertility rates, marriage rates crashed by 20% in 2024 over the previous year to reach its lowest level since 1986. Earlier this week, the government decided to withdraw exemptions granted three decades ago to contraceptives and remove taxes on childcare and marriage services.

In South Korea, which has the world’s lowest fertility rate, the number of marriages has declined by an astonishing 40% between 2013 and 2023.

Japan is recording the lowest number of births in a century as marriage rates crashes,

In the US, finds Pew Research in a report published on November 2025, 12th grade girls are less likely than boys to say they want to get married, 61% to 74%.

One in seven young adults in the EU now lives alone. Declining birth rates are not so much because couples are opting to have fewer children but because there are now fewer couples. “The central demographic story of modern times is not just declining rates of childbearing but rising rates of singledom,” notes the financial times.

The India story

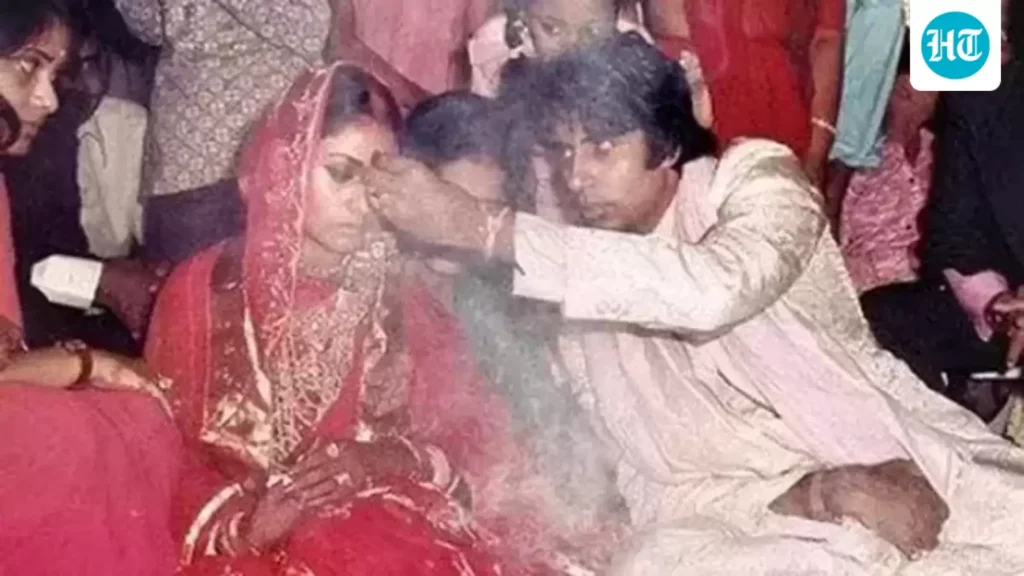

India’s marriage story is very different. A society that prioritizes family over individual choice, has ensured that marriage remains central to the lives of most Indians as it continues to be conducted in line with caste, class, faith and socio-economic status. In fact, 95% of all marriage decisions are shaped by families, finds Sonalde Desai, sociology professor, National Council of Applied Economic Research.

In 40% of these marriages, women do not have a say in their choice of partner; 65% meet their husbands for the first time at or around the wedding.

“I don’t see any sign of a declining interest in marriage in India,” says Desai, who has conducted the India Human Development Survey of 41,554 households in 1,503 villages and 971 urban neighborhoods since 2003.

Bengaluru-based relationship coach Simran Mangharam agrees. “Everyone who comes to me, man or woman, wants to get married…There is still in our culture a lot of talk about ‘settling down’.”

Yet, things are changing and this generation’s marriage is likely to look very different from their grandparent’s in at least three significant ways.

The first, child marriage is down from 47.4% in 2005-6 to 26.8% in 2015-16—a decline of 21 percentage points in a decade, finds data from the United Nations Population Fund.

The second is that men are marrying later. Because of economic changes, including unemployment, men are being forced to wait longer and even sometimes pay to tie the knot, finds a 2022 paper by Alaka Malwade Basu and Sneha Kumar. While this has not, yet, resulted in a modernizing overhaul, it could in the longer run tip the marriage market more towards women, finds the paper.

And the third significant, and most welcome, change is the greater input by women in their marriage decisions, with 55% now being consulted by their families. The more educated the bride, the greater her voice. In Desai’s study, 77% of graduates provided inputs to their families.

“Even though the desire for marriage and child-bearing is not changing,” says Desai, “There is a lot of change in family dynamics and this is to be welcomed.”

modern marriage

While the institution of marriage itself shows no sign of dying or even slowing down, an increasing number of women are questioning its validity in modern life.

A new generation of aspirational women, armed with education, increasing workforce participation, financial independence and changing social norms, are beginning to ask the questions: Why does the burden of care work fall largely on one gender? Is it wrong to be ambitious? How does marriage impact careers? What is this unrealistic pressure to produce children, and who should bring them up?

And the big one: Why should marriage be central to our lives?

The fact that fewer women than men raised their hands to Upasana Konidela’s question on whether they wanted to marry, also indicates the awareness of women of the sacrifices and disproportionate burden of care work that continues to fall on them. “Women in their 20s are fearful of losing their freedoms, the way their mothers did,” says Mangharam.

Marriage equality also remains a demand for many from the LGBTQ community that wants the same rights as heterogenous couples such as the right to adopt jointly, name partners as beneficiaries in insurance or take critical life and death decisions on behalf of a partner.

Jaya Bachchan is right. Marriage as we know it is in need of an overhaul. It may not have yet happened in India—as it is in other parts of the world—but change is coming, and it will be led by women.