In an increasingly grim and ghastly world of Jeffrey Epstein, impunity for rapists, and gender pushbacks, Gisele Pelicot is a beacon of hope.

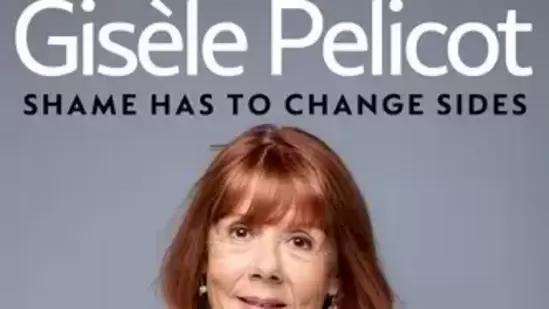

She doesn’t like that expression, she’s said in interviews in the run up to the release of her book, Hymn to Life: Shame must change sides on February 17. She rejects the words ‘hero’ and ‘icon’.

“I prefer the word ‘symbol’ because what I value now is having given a voice to women,” she told British Vogue.

To Lulu Garcia-Navarro who interviewed her for the New York Times, Pelicot talks about the legions of women who would turn up at court in Avignon where her husband Dominique Pelicot faced trial for drugging and raping her and facilitating her rape by over 70 men, 51 of whom also stood trial since not all were found.

“This trial echoed their suffering,” Gisele says. Morning after morning the women would turn up in rain, in cold: “It touched me deeply. Their presence outside the building softened what was happening for me inside the courtroom.”

The Gisele Pelicot story is mandatory reading for anyone with even a passing interest in gender justice. It is the story of an ordinary woman against whom an unspeakable crime was committed, not once but repeatedly for nearly a decade from 2011 to 2020; not by a stranger but by her own husband.

The men he invited to rape her in their home included a nurse, teacher, firefighter, journalist and even a prison warden. In 2020, police arrested Dominique for taking photographs up the skirts of women at a supermarket. When they examined deeper they discovered the shocking crime. Gisele Pelicot was called into the police station to learn that the man she had been married to for 50 years was in fact a monster.

Changing the rape narrative

The Gisele Pelicot story gripped me from the beginning. At first it was the shock of the nature of the crime. But it is what the now 73-year-old grandmother did next that was even more extraordinary: She waived her legal right to anonymity. In doing so she ensured the rape trial would not be held behind closed doors. She was clear, the shame of it was not on her but on them. She wanted the world to know what these men had done.

In doing so, Gisele Pelicot single-handedly changed the narrative on how we talk about rape.

[I wrote about Gisele Pelicot in a September 2024 column just as her trial started and she had waived anonymity. That column is here.]

In much of the world and definitely in South Asia, rape is seen as a loss of ‘honour’, not just of personal honor but that of a woman/girl’s family and even of her community. The anonymity granted to women and girls in India is premised on this loss of honor and to protect her privacy. In Indian courtrooms, judges have been known to counsel rape survivors to marry their rapists—because who else will?

Gisele Pelicot’s case is exceptional in its visibility. The violence itself is not.The United Nations tells us that globally in 2024, 137 women and girls were killed a day by someone in their own family. One in three women is subjected to domestic violence. These are numbers that roll off the tongue, repeated so often as to lose their impact. If Gisele Pelicot was just an ordinary woman, the violence against her was also a routine crime.

Dominique Pelicot recruited men to rape his wife in a chat room called Without Her Knowledge on a website that was founded in 2003 and shut down in 2024. It’s like a sickness spread all over the world. In August 2025, Facebook removed an Italian group where men shared intimate images of women without their consent. The group with 32,000 members was called Mia Moglie, my wife. Two months later, Italy’s Parliament delayed debate over a law that would define sex without consent as rape. Matteo Salvini, deputy prime minister said the law would “clog up the courts”.

If the Pelicot trial exposed the lie of marital consent, India continues to cling to it. Lawmakers have refused to criminalize marital rape for fear, they say, of destroying the sanctity of marriage. This past week, a man sold his wife for ₹1,000 to two of his friends in Uttar Pradesh.

In the UK, Philip Young, a 49-year-old former Tory councilor has been charged with drugging and raping his wife and letting at least five other men rape her between 2010 and 2023. The survivor, Joanne Young has waived her right to anonymity.

Gisele Pelicot’s stand is what makes her extraordinary. Look, she is saying, a terrible thing was done to me. But I am not to blame. And I will fight for the justice I deserve.

In choosing an open trial, Gisele also showed the world what a rape trial can look like. A lawyer for one of the rapists asked her in court if she had “tendencies you are not comfortable with”, implying that she was somehow complicit in this horrible crime. It’s this sort of questioning that leads to 94% of rape complaints in France being closed without action taken. It’s a universal tale. A woman who complains of rape becomes the object of scrutiny: What was she wearing, why was she out so late at night? She is counseled to stay at home when we know emphatically that the home can be the most dangerous place for women.

Light and hope

Yet, for all its darkness, the Gisele Pelicot story is one of light. Light shed on the layers of hypocritical social attitudes that surround the crime of rape.

Light shed on how oblivious men can be to their crimes—several defendants told the judge in court that since they had the consent of the husband, they assumed they had the consent of the wife.

And the light of justice. Dominique Pelicot has been sentenced to 20 years in prison, the other men have received between three and 15 years. Not enough felt many including Pelicot’s three children. But she is happy justice has been served. “All of them were found guilty. It was a victory for me,” she says.

In October 2025, a year after the Pelicot verdict, France finally changed its rape law to add consent.

But there is lightness too in the resilience of Gisele Pelicot. The moral clarity of her vision, her grit to fight the good fight and her refusal to be broken.

It is in affirming life and defying every meaning of the word ‘victim’, that Gisele Pelicot is at her most triumphant. “I was able to heal myself,” she says. “I’ve given myself permission to be happy.”