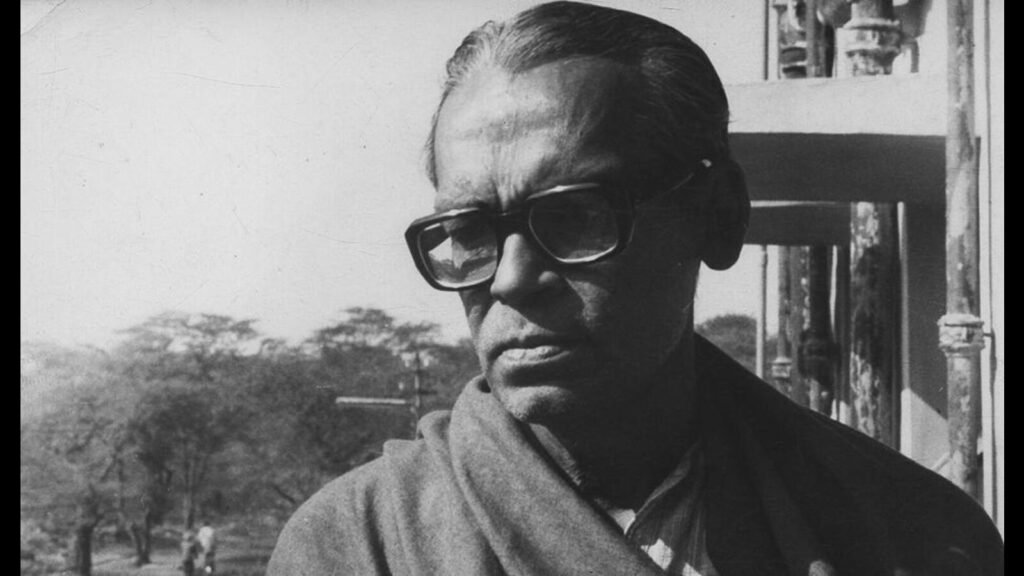

Charaiveti, CharaivetiWith these enchanting words (which means keep moving) from the Aitareya BrahmanaRitwik Ghatak’s film Subarnarekha (Golden Thread) begins as a scroll moves upward showing the credit titles on screen. While our eyes move, our auditory senses get immersed in some unpredictable temporality. The creator of the film has established his signature right at the outset. Obviously, it has broken a convention. Through his filmmaking practice and writings, Ghatak (November 4, 1925-February 6, 1976) has made the younger generation of filmmakers fearless in taking artistic risks. That is his great legacy to not only Indian but world cinema. In this year of his birth centenary, though technology has made many inroads into the creative processes, Ghatak shows us an alternative path which is enduring. His voice needs to be heard in our globalized world getting increasingly divided.

The Partition of Bengal had emotionally pained him so much that he articulated that pain with unique poetic pathos in his oeuvre of only eight completed feature films. Today, each of these films — citizens (1952), Ajantrik (1957), Bari Theke Paliye (1959), Cloudy Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961), Subarnarekha (1962), Titas Ekti Nadir Naam (1973) and Jukti Takko Aar Gappo (1974) — is being seen and studied in universities and film schools across the world. But in his lifetime, Ghatak was never invited by any foreign film festival or an institute to present his work and talk about cinema. Today, Cloudy Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar,and Subarnarekha are shown and studied as the Partition trilogy. In these films, Ghatak aesthetically amalgamates mythology and history that deeply humanises cinema on an epic level.

How should Ghatak’s legacy be celebrated in his birth centenary year? No matter, he worked in the analogue times, we can still undoubtedly highlight certain elemental markers that remain constants — for instance, melodrama, mythology, being an epic, use of songs and sounds, use of lenses, defying the dictatorship of the market, use of the archetype, and being poetic, away from didacticism and even scripted pre-determinism. This astapadi (eight steps) of sorts is exemplified by the creative output he has left behind, restored and archived

In fact, Ghatak had completed his first feature film. citizens (Citizen) in 1952 but unfortunately its prints were lost and the film could not be released on time. It could be released only after his death, in 1977. Had it been released soon after its making, it would have preceded Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955) and that would have changed the narrative of Indian cinema history. Ghatak knew every aspect of filmmaking, including camera operation and the optics, and was an accomplished actor both on stage and screen — his role as Neelkanth Bagchi in his last film. Jukti Takko Aar Gappo is considered to be so pure and pristine, writing his own autobiography. There were a few departures in Ghatak’s life — for instance, joining Filmistan studios in (then) Bombay under Shashadhar Mukherjee. His letter to Mukherjee suggesting several radical changes to provide space for experimental filmmaking is a much-talked about document today. During his stay in Bombay, Ghatak wrote the script and scenario for Bimal Roy’s film. Madhumati (1958) and also collaborated with Hrishikesh Mukherjee on traveler (1957). During 1966–67, he had a brief stint at the Film Institute of India (later Film & Television Institute of India) as professor of film direction and vice principal.

Ironically, Ghatak, who gave up theater for cinema to reach the largest number of people, saw his films failing at the box office even in Bengal. In his foreword to Cinema and I, a collection of Ghatak’s writings on cinema, Satyajit Ray writes, “Ritwik had the misfortune to be largely ignored by the Bengali film public in his lifetime. Only one of his films, Cloudy Dhaka Tara (Cloud-capped Star, 1960) had been well received. The rest had brief runs, and a generally lukewarm reception from professional film critics. This is particularly unfortunate, since Ritwik was one of the few truly original talents in the cinema this country has produced. Nearly all his films are marked by an intensity of feeling coupled with an imaginative grasp of the technique of filmmaking. As a creator of powerful images in an epic style he was virtually unsurpassed in Indian cinema.”

Ghatak’s originality that Ray is talking about is difficult to emulate but it still functions as a pathfinder. The way he improvised shots and scenes on the spot while shooting was extraordinary. Take the bereft at the abandoned airstrip scene in SubarnarekhaIt was not in the script at all. And the way he embroidered Rabindranath Tagore’s song Today Dhaner Khete Roudro Chayay and the tale of the Ramayana in this scene, will defy all the set theories of the so-called cinema language.

We can cite many examples from Ghatak’s films that can be easily called unparalleled in world cinema today. And they were accomplished with scarce means, never in his filmmaking career he had the luxury of money at his disposal. How to become inventive in the face of adversities is yet another lesson that young filmmakers can learn from him.

Ghatak’s ideas about epic cinema are much discussed. What did he mean by epic cinema? In his essay “Music in Indian Cinema: An Epic Approach”, Ghatak talks about an epic attitude: “…we are an epic people. We like to sprawl, we are not much involved in story-intrigues, we like to be re-told the same myths and legends again and again. We, as a people, are not much sold on the ‘what’ of the thing, but the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of it. This is an epic attitude.” Ghatak, a great raconteur, gives us an example of the Greek filmmaker Michael Cacoyannis and his film Electra“Significantly, the subject is from the old Greek master, Euripides — because the script is strictly based on the Oresteian tragedy.”

Through his cinematographic oeuvre, Ghatak has grandly created an ensemble of archetypes which, to him, led to the poetics. He said, “The poet is the archetype of all artists. Poetry is the art of arts.” With archetype, Ghatak talks about collective consciousness as propounded by the psychoanalyst Carl Jung. In his films, Ghatak, as Ray says in his foreword, “lays particular stress on aspects which are not obvious on the surface: such as what he derived from an early study of Jung — the use of the archetype, the mother image, and even the concept of rebirth.”

Ghatak was the poet of our cinema. He was born in the year when his favorite filmmakers, Sergei Eisenstein and Charlie Chapin, had come out with their films, Battleship Potemkin and The Gold Rush,respectively. The year 1925 was a year of the archetype. Ritwik Ghatak was the Euripides of Indian cinema.

Amrit Gangar is a Mumbai-based author, curator and historian of cinema. The views expressed are personal