A visit to the beautiful state of Karnataka that I am privileged to represent in the Council of States — a land whose very name evokes images of lush green landscapes, waterfalls, ancient hills, verdant valleys, pristine rivers, and a history that stretches back millennia — is always invigorating. This visit was a journey through time, a study in contrasts, and a powerful reminder of our nation’s immense potential.

My first stop was the historical site of Hampi, located in the newly formed Vijayanagara district. The ruins of Hampi stirred in me both awe and melancholy. Once the magnificent capital of the Vijayanagara Empire, Hampi was described by the Portuguese traveler Domingo Paes, who visited around 1520–22 during Krishna Deva Raya’s reign as “the best provided city in the world”, of its capital as being “as large as Rome, and very beautiful to the sight,” a city “full of riches and precious stones… where they sell everything”.

From the magnificent desolate ruins of Hampi, I traveled into the Kalyana-Karnataka region, whose geography itself tells a story of extremes. Within Kalyana-Karnataka, the Krishna-Tungabhadra doab is a lush-green landscape with paddy fields, sugarcane and banana plantations breaking the monotony of the precariously perched red-brown granite boulders and further into the hinterlands lay the vast dry country, infamous for its droughts. Historically, most of Kalyana-Karnataka was part of the Hyderabad State (excluding the united Ballari district, earlier under Madras Presidency) and still bears the scars of the Nizam’s misrule. Kalaburagi, for instance, has the lowest per capita income in South India, and both of Karnataka’s aspirational districts — Yadgir and Raichur — belong to this region. Planning here must therefore be sensitive to stark local variations. This is where the government of India’s Aspirational Block Program plays a crucial role, focusing not only on districts but also on sub-district and block-level disparities.

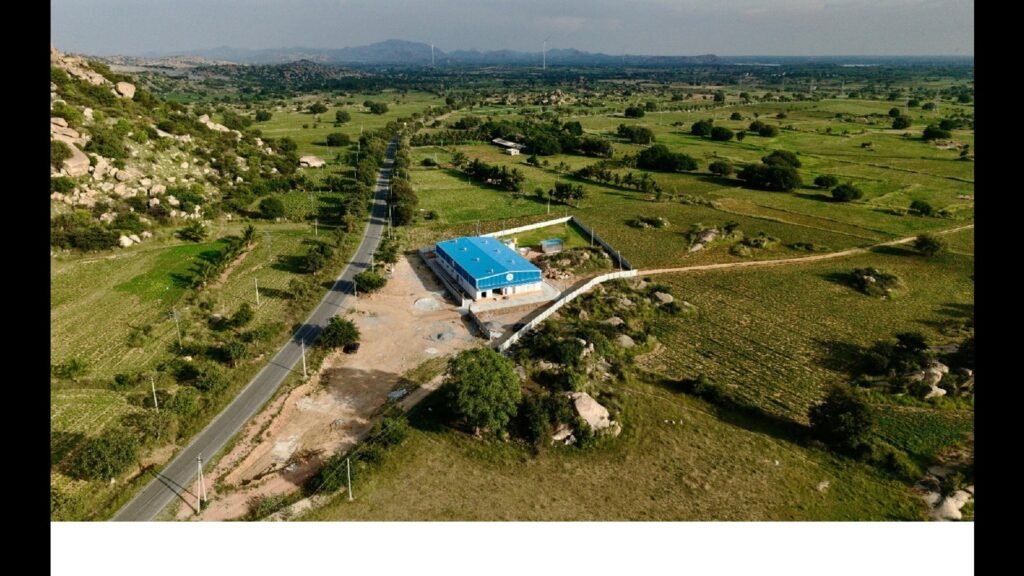

My MPLADS funds were leveraged to support farmers of the region by bringing agro-processing capabilities to their doorstep. An umbrella brand of Kalyana Sampada (Wealth of Kalyana) was created, and each district was encouraged to identify an agri-product or a set of products that could be developed into value-added. commodities. The initiative aligns with the Prime Minister (PM)’s vision of “One District, One Product” program as an extension of Make in India for our annadatas (farmers). In each district, a farmer producer company (FPC) was chosen by Nabard to operate the food processing and training units.

In Koppal, where per capita income is about 15% below the national average, a multi-fruit processing unit has been established. Although the district cultivated about 6,000 hectares(ha) of mango, 5,000 ha of papaya, 3,000 ha of guava, and 2,000 ha of tomato, it lacked processing facilities. This is the first fruit-processing unit in the district, which now processes these fruits into products such as mango juice, dry mango powder, guava nectar, tomato puree, and ginger powder, ensuring farmers gain from value addition. The unit can process only about 2% of the fruits to juice/pulp produced in the district, and there is immense potential for many more units in this district.

In Raichur, an aspirational district known for its large pulse production — over 80,000 metric tonnes of red gram and 34,000 metric tonnes of Bengal gram annually — the new processing unit focuses on converting these pulses into arhar dal, chana dal, and a ready-to-make chilla mix. The unit can procure-process-market about 1% of the total pulses produced in the district. At least 50 such units would be required to process about 50% of all the dal produced in the district. This initiative, therefore, serves as a model for other FPOs and rural entrepreneurs in the district to emulate.

Ballari, Karnataka’s chilli capital, produces about 44% of the state’s dry chilli. The Siruguppa block here contributes the maximum cultivated area, yet farmers have to transport their harvests nearly 250 km to Byadgi market — a journey of over five hours. To address this, we established the first chilli processing unit in Siruguppa. Supported by funds from my MPLADS allocation, Nabard assistance, and a 12 lakh contribution from the Siddagangashree FPC, this facility is a fine example of Jan Participant — citizen participation in development. The chairman of the FPC, Ambresh Gouda shared his excitement that farmers across the taluk have been calling him about selling their produce locally, and that they are happy to have modern machinery to process. chili. The unit has received orders of nearly three tonnes of dry chilli powder from across India — another first for this region. Mallamma, a chilli farmer, expressed happiness that they will now process their chillies and market them under their own brand.

In Vijayanagara district’s Kudligi taluk — among the driest regions of the southern peninsula — the story is one of resilience. Despite low rainfall, the people have shown remarkable foresight; their centuries-old tamarind trees yield fruit, forming the backbone of livelihoods in the dry season. Planting and nurturing more tamarind trees would support livelihoods. Groundnut is cultivated in over 33,000 hectares, mostly on impoverished soils with erratic rainfall. Further, farmers face the risk of attacks from sloth bears. The newly established center focuses on producing peanut butter, roasted peanuts, chikkideseeded tamarind, and tamarind pulp. The FPC plans to add an oil press to produce groundnut oil.

For decades, cooperative movements in states like Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Karnataka have served India well. FPCs build upon the strength of collective action, infusing it with corporate discipline and governance. Owned by farmers and structured to compete in modern markets, they embody the next era of India’s agricultural transformation. Interacting with these FPC members, I could sense their vitality and confidence — ready to seize the promise of Viksit Bharat.

This approach perfectly complements the PM’s call for becoming “vocal for local”. When each village learns to process its own produce, the results multiply. Farmers gain higher, stable prices for their crops, neighboring youth find local employment, and rural communities acquire new technical and business skills. At Koppal’s processing unit, I met Aishwarya, the CEO of Gavisiddeshwara FPCL, a young BTech from Kinnal, well-known for its GI-tagged wooden toys. She spoke confidently and guided me through their operations. Her enthusiasm was infectious. She embodied the spirit of self-reliant, aspirational young India.

These units are located in the rural heart of some of India’s most underdeveloped areas. Every FPC prioritizes employing local youth, creating a cycle in which profits and growth circulate within the same community. The result is not just economic progress but a restructured sense of dignity and self-reliance. During one interaction, a director of an FPC told me something deeply moving: He no longer receives rations under the Public Distribution System because he is now a company director. It had a rare mix of emotion — the loss of a benefit that gave a feeling of security versus the pride of earning with one’s own effort, now that opportunity and access were made available. That transformation — from a welfare beneficiary to a business leader — is the very essence of empowered growth we must aim for, across the nation.

Agro-processing today demands capital, technology, and market linkages. In an increasingly protectionist global environment, strengthening our domestic food processing capacity is a national security priority. Self-sufficiency in food processing ensures resilience against global disruptions and creates rural prosperity in tandem.

India is primed for this leap. In the true spirit of cooperative federalism, the Center and states must join hands to scale and replicate these successful models nationwide. The path to Viksit Bharat will be built not merely in cities or industrial hubs but across our villages — by empowering farmers as entrepreneurs, by converting every district into a processing hub, and by ensuring that the fruits of India’s progress reach every household.

Nirmala Sitharaman is the Union finance minister. The views expressed are personal