It is quite the irony that while Aloka — the Indian stray dog adopted by a band of Buddhists monks — is being cheered worldwide for walking thousands of miles in the US alongside the monks in their march for global peace, his counterparts in India are being subjected to cruelty by the very institutions that should protect them.

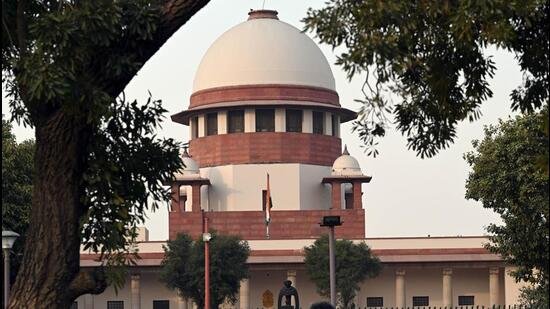

Over the past few months, the Supreme Court has taken a keen interest towards managing the so-called menace caused by stray dogs in India. The Court has issued a slew of directions that are not only inhumane, unscientific, and non-implementable, but also defeat existing legislation on the matter, viz. the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act and the Animal Birth Control (ABC) Rules framed therein.

Institutions constituted to protect certain rights may often fail to preserve these, but what happens when such failure spreads across all pillars of democracy — the executive, the legislature and the judiciary? What happens when judicial overreach and activism assume the role of the State without adequate data or material, and decide the fate of voiceless animals? Perhaps the doctrine of parents patriots has lost its meaning, and now lends its weight to the rights of those who can speak and fend for themselves, instead of supporting the voiceless. (Under the principle of parents patriotsa State or court has a paternal and protective role over its citizens.)

As per the Constitution, it is the fundamental duty of every citizen to have compassion for all living creatures and mete out humane treatment to them. These principles are embedded in the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, formulated in 1960 and the ABC Rules 2001 (amended 2023) that prohibit permanent confinement of stray dogs, which would cause them unnecessary pain and suffering.

Instead of ensuring implementation of the extant law and compliance by the executive, the judiciary has tasked itself with resolving the so-called stay-dog menace by directing permanent confinement of stray dogs found in institutional areas, such as educational institutions, railway stations and hospitals. Such an order, which is beyond the realm of law, can never be implemented, especially when there is barely any infrastructure in the country to support animal birth control in non-metropolitan cities.

In a country where a large number of homeless people often don’t find shelter from the biting cold in winter and children don’t get sufficient mid-day meals in schools, adequate shelter for permanent confinement of stray dogs — offering enough food, water and medical care — seems even unlikely.

It is important to emphasize here that nobody arguing for the strays is ignoring the problem of the rising stray-dog population in the country and the incidents of dog bites and attacks on people. But when the law already has strong enough provisions to deal with a dog that may be demonstrating aggressive behavior, why should all community animals be painted with the same brush and be punished in a heartless manner? Even the accused in some of the most shocking crimes committed by humans have received a fair trial and were heard. Ultimately, that is what our Constitution guarantees to all.

Anyone who works in animal welfare understands the challenges faced in accessing care facilities, given the marginal availability of government facilities. Against such a backdrop, is it even realistic to imagine having shelters for strays in the scale needed to comply with the orders of the Supreme Court?

Stray dogs throng the roads of our cities primarily due to the lack of effective implementation of the ABC Program by the authorities, under the ABC Rules. Why isn’t the Court taking action against the persons responsible over the last several years for carrying out the ABC Program across India? Shouldn’t it be taking steps to correct the pathological state of affairs in the country’s animal birth control centres? Strangely, the Animal Welfare Board of India, in a stark departure from the accepted principle of curbing stray-dog population through sterilization of female dogs, now wants to shift the focus to the sterilization of male dogs, that too on priority.

The scientific and humane approach followed all over the world is being undermined in favor of an inhumane and unscientific approach. There seems to be stubborn amnesia with regards to compassion for living creatures and the constitutional provisions encouraging the same. You can hate an animal, or you can be indifferent, but when you are dealing with the rights of thousands of sentient beings and deciding their fate as a constitutional court, humanism ought to be exercised.

This is why, every stray dog in India would wish it were Aloka. While the world cheers Aloka and his journey to spread peace, our strays cry for help. They too are deserving of peace and compassion, and would be hoping that some mercy be shown to them by the Supreme Court.

Gauri Puri is an advocate practicing in the Supreme Court of India. The views expressed are personal